Where have South Africa’s white sharks gone? And where do they go when orcas move in?

These are two of the most frequent and pressing questions we’re asked following the dramatic and well-documented disappearance of white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) from historical aggregation sites such as False Bay, Gansbaai, and, more recently, Mossel Bay. Evidence suggests this disappearance is driven mainly by predation and predation risk from orcas, particularly the infamous pair, Port and Starboard (Engelbrecht et al. 2019; Towner et al. 2022a, b; 2024), though other environmental and human-related factors may also play a role.

A close-up of one of the 11 white sharks encountered in Mossel Bay prior to tagging. (Photo: Melissa Nel, Shark Spotters)

One of the biggest scientific challenges has been determining where these sharks have gone. Sightings have been sporadic, making access difficult, and existing acoustic transmitters are no longer being detected on inshore receiver arrays. Two expeditions in 2024, to Struisbaai and Plettenberg Bay, yielded no success. With limited satellite tracking data in recent years, their movement patterns have remained frustratingly elusive.

On 10–11 April 2025, we teamed up with marine biologist Don Marx (Southernmost Apnea) aboard White Shark Africa’s research vessel to deploy Mini-PAT (pop-up archival) satellite tags from Wildlife Computers on white sharks in Kleinbrak, Mossel Bay. The tags are deployed externally using a bait lure and a specially designed tagging gun, eliminating the need to capture or restrain the animals. This low-impact approach reduces stress while still delivering high-quality data on their three-dimensional movements.

Mini-PAT satellite tag attached to a white shark, captured shortly after deployment. (Photo: Melissa Nel, Shark Spotters)

Each tag records light levels (used to estimate location), depth, and temperature over six months. Once detached, no matter where in the world, the tag transmits a summary of the data to the Argos satellite system. However, if the tag is recovered, the whole dataset can be downloaded and refurbished for future use. This method has been successfully used before, most famously on Nicole, the white shark that completed a transoceanic journey to Western Australia, and more recently in 2023, when a shark tagged in Struisbaai travelled between Alphard Banks and the Agulhas MPA before returning to the original tagging site, where the tag was recovered.

Although we initially planned to tag sharks in East London, based on reliable sighting reports, a sudden increase in white shark activity in Mossel Bay provided an unmissable opportunity and more favourable logistics. Over just two days, we encountered 11 individuals ranging from 1.8 to 3.8 metres in length and successfully tagged eight. All tagged sharks either remained in the area or returned to the vessel, allowing us to confirm tag placement and attachment visually.

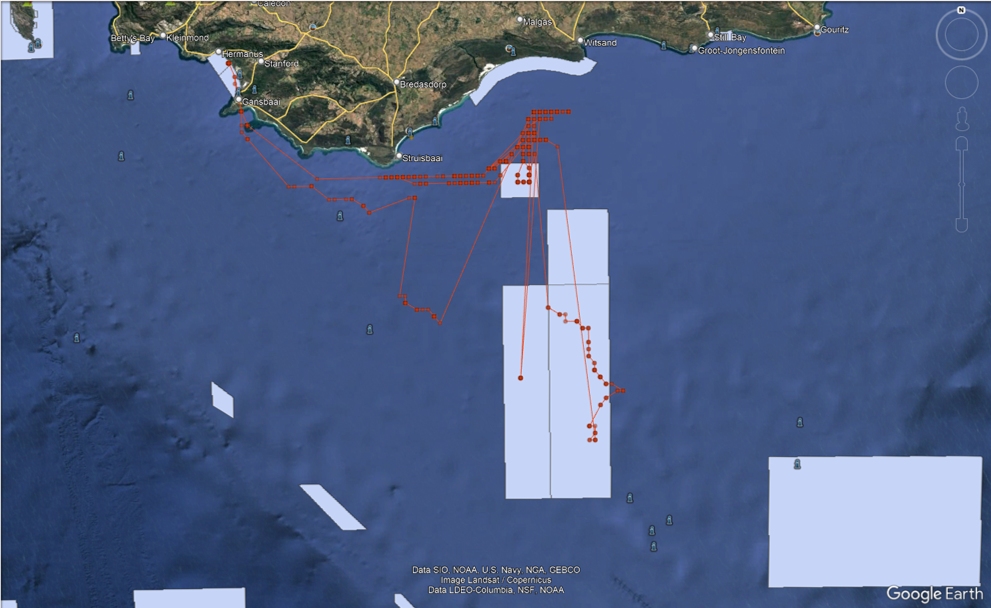

Track of a white shark tagged in Struisbaai with a mini-PAT satellite tag.

Now begins the waiting game, a familiar part of ocean science. Studying large apex predators and deploying research equipment in the ever-changing marine environment involves many factors. These include the tags remaining securely attached, the sensors functioning correctly, the saltwater switch activating, successful detachment, the tags floating to the surface, and reliable communication with the Argos satellite. With the satellite tags successfully in place, we must now wait six months until they detach and transmit their data. What they reveal will be invaluable in deepening our understanding of white shark movements and habitat use and shaping more effective conservation strategies as these iconic predators adapt to a rapidly changing ocean.

This work was made possible thanks to the incredible field support of White Shark Africa (Eric, Christo, Caleb) and Go Dive (Elton), as well as the collaborative support of South African Environmental Observation Network (NRF-SAEON) Egagasini Node, South African Polar Research Infrastructure (SAPRI), Department of Science, Technology and Innovation (DSTI), South African Institute of Aquatic Biodiversity (NRF-SAIAB), South African National Parks (SANParks), South African International Maritime Institute (SAIMI), Shark Spotters, Ocean Charters, Oceans First Institute, the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE), and Warner Brothers Discovery.

Text supplied by Alison Kock (SANParks and NRF-SAIAB) & Alison Towner (South African International Maritime Institute)

Rabia Mathakutha, South African Polar Research Infrastructure, 30 April 2025